SPECIFIC REVEGETATION DESIGN PRINCIPLES

When designing and planning a revegetation site, the details depend on your specific goals. It might be tempting to believe there’s a universal ‘recipe’ for revegetation that works everywhere, but it actually varies based on what you’re trying to achieve and the unique features of each site.

There are a couple of principles that apply to all revegetation – fencing design, size and shape, fire and climate readiness. The rest of the chapter addresses different revegetation types and principles of design for those different goals.

Fencing design

Fencing is the tool we use to exclude grazing animals from revegetation areas. It is the most expensive part of a revegetation project, but also the most important for success. Fencing style is a personal preference based on your landscape, livestock, stocking rates and budget. Revegetation takes at least five years to establish, so the fence must remain stock-proof for at least that time.

Funded projects may have minimum or specific criteria and require permanent fencing, and wildlife-friendly fencing is best practice for biodiversity plantings.

Permanent vs. temporary fencing

- Permanent: uses strainer posts driven into or cemented in the ground plus wires or mesh. . It should be stock-proof without electricity.

- Temporary: often relies on electricity to keep animals out.

Wildlife-friendly fencing

Wildlife-friendly fencing removes the risk of wildlife being injured or killed in a fence that is put up to protect them, and allows for free movement of wildlife in the landscape.

A wildlife-friendly fence will:

- have no top barbed wire

- avoid barbed wire altogether, if possible

- avoid buried netting or low electric wires at the base of the fence (look after echidnas and wombats)

- be standard height.

Exclusion fencing is only appropriate for revegetation and remnant-protection fencing on farms in specific circumstances, such as exclusion of pest animals for wildlife reintroduction.

Other considerations

- Larger blocks are cost-effective – fewer strainers, greater value for money.

- Always include gates for access and to manage fire risks.

- Consider preparing the site before fencing.

Find out more…

WIRES: Wildlife-friendly Fencing – https://www.wires.org.au/wildlife-information/wildlife-friendly-fencing

Macedon Ranges Shire Council – Wildlife-Friendly-Fencing-Brochure.pdf

LLS Factsheet (link to come)

Site Design

Size and shape - Configuration

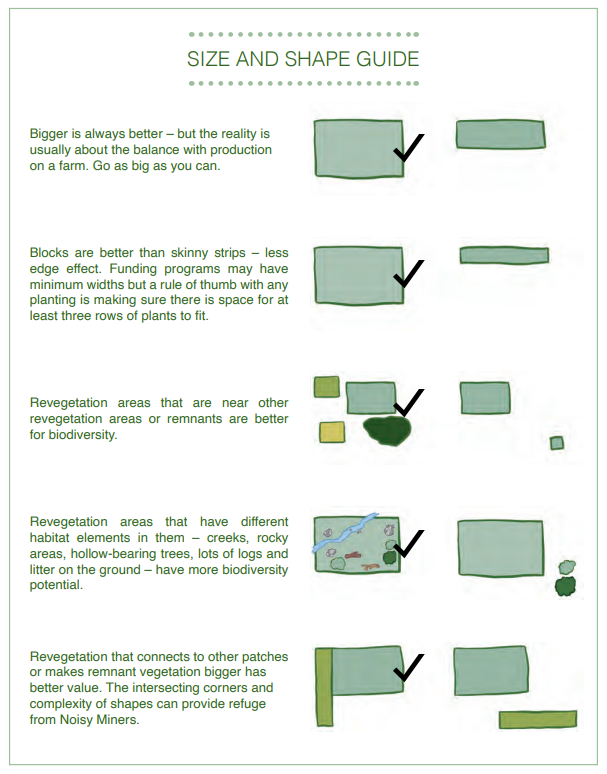

All revegetation is good in the landscape, but research shows that the width, length and the way blocks connect matter for biodiversity outcomes.

In small plantings there is an ‘edge effect’, which means the outside of the planting is more influenced by wind, heat and what’s going on in the paddock (e.g., overspray, fertilising). The edges are favoured by some species, avoided by others and are areas where predators are more prevalent, so very narrow plantings may not have as much biodiversity value as wider sites. There are also cost efficiencies in bigger block plantings.

In the South West Slopes we have good data on the effectiveness of revegetation for birds, reptiles and arboreal mammals and an insight into what size, shape and characteristics of revegetation are most effective thanks to the Australian National University’s long-term monitoring.

This graphic has been adapted from a great resource, Managing natural assets: shelterbelts, Sustainable Farms, an initiative of Australian National University, 2023.

Figure 5: Size and shape (configuration) and biodiversity outcomes [Adapted with permission: ANU Sustainable Farms]

Find out more…

Ten Ways (link to come)

Sus Farms books (link to come)

ANU papers (link to come)

Bennet papers (link to come)

Fire Readiness

Fire readiness in design is all about access in an emergency.

- Always include gates – for gaining access to fires, or getting stock out in an emergency.

- Plan breaks – avoid long continuous linear revegetation areas without breaks – make sure paddocked gates are still accessible.

- Wider plots are easier to get stock in and out of. Stock may head to wet gullies or creek areas in a fire for refuge and can be rounded up and driven to safety so they don’t become trapped.

In some cases, revegetation areas can be helpful in managing fast-moving grass fires in that they can slow fire spread enough to get resources there. Revegetation areas can be placed strategically to reduce wind speeds and therefore the speed of fire spread.

Individual fire behaviour varies widely depending on the conditions at the time, and in a catastrophic fire event, no level of ‘design’ is going to help. The most important thing is to have a realistic view of fuel hazard and risk in your revegetation areas and a fire plan for your property. The NSW Rural Fire Service (RFS) provides many resources.

Fire as a tool for management of vegetation is covered here…

Find out more…

Florabank Guidelines – https://www.florabank.org.au/

Climate readiness

These use plant species and sources that match expected future climate conditions.

The steps for designing climate ready plantings are:

- Understand climate projections for your region and site

- Identify your climate analogue – find the region your area will resemble climatically in the future (e.g., 2030, 2050, etc.)

- Use the revegetation guide to choose 5 to 10 species that occur in both areas

- Get some of your plants and seeds from the analogue area.

In general, seed or plant stock in a planting for climate resilience should be 70 per cent local and 30 per cent from climate analogue areas.

Border Ranges Richmond Valley Landcare Network project (Duration: 3.11 minutes)

Creating a climate adaptive haven (Duration: 3.12 minutes)

Seeds of Resilience (Duration: 3.29 minutes)

Climate resilient landcare projects (adapting plantings to extreme flooding) (Duration: 8.57 minutes)

Wirraminna climate plots video (link to come)

Sourcing Seed and Plants

In general, using locally sourced plants or seed for revegetation is important to ensure plants are adapted to local conditions and maintain local genetic diversity as well. However, there are some exceptions to this – for example:

- adaptation for climate resilience where you might choose to include plants sourced from a climate analogue area, or

- if local populations of plants have become isolated and you need to introduce more genetic diversity.

But even then the majority of revegetation should still be based on local species and local plants and seed where possible. ‘Local’ really means collected from the closest remnant populations. Sometimes this is possible, but if it is not, then choose plants grown from a similar landscape or climate analogue region. The latest best practice in seed and plant sourcing can be researched in the Florabank Guidleines.

Biodiversity plantings

Biodiversity is a term for the diversity of life – the soil organisms, plants and plant communities, and the range of insects, birds and animals that may live in a certain place. Once we have protected the good stuff (near-natural and less degraded sites) then we may want to improve other sites or plant new sites.

Biodiversity plantings aim to improve biodiversity in the landscape by:

- adding plants and structure to existing patches in poor condition

- connecting patches so fauna can move around

- creating new patches.

For biodiversity restoration and revegetation in general:

- use wildlife-friendly fencing to control livestock access – grazing impacts the quality of remnant vegetation and the success of revegetation (Lindenmeyer et al., 2018)

- bigger is better – use the ‘size and shape’ principles mentioned in Figure 5

- maximise diversity – plant a range of trees, tall, medium and small shrubs, groundcovers and grasses if the site is suitable

- you don’t have to plant in lines – clumps of shrubs and habitat patchiness is good for many species

- include plants that are nectar sources for natural predators and pollinators

- control weeds – environmental and invasive weeds can take over plantings

- implement pest-control programs to reduce the impact of animals (rabbits, hares, deer, goats, pigs) on the plants and the wildlife

- cultural connection – research and encourage traditional cultural practices and connection with Country, including the use of cultural and ecological burning (see Fire as a management tool in Chapter 7).

To maximise the biodiversity benefit on your farm you need a wide variety of habitat types, including protected remnant vegetation and revegetation areas of varying ages.

It is possible for revegetation to have negative impacts on species if they need a specialised habitat that does not include not trees and shrubs – for example, many grassland species. In general, this will only be relevant in very specific local areas. Speak with your Landcare and/or local regional natural resource management agency for more guidance if you are worried.

Find out more…

Creating Habitat havens factsheet (link to come)

Planting Around rocky outcrops.

Rocky outcrops can be:

- Refuge areas for many species e.g., hilltopping butterflies.

- Specific habitat for some species e.g., Carpet Pythons and many other reptiles.

- Culturally significant and so provide an opportunity to learn more about the stories of your place

To protect and enhance rocky outcrops consider the following:

- Use wildlife friendly fencing to protect from livestock

- Prevent any rock removal

- Protect from fire – Keep prescribed burning out of the area to prevent damage to rock condition, and animals that refuge there

- Control pest animals that also use it as refuge. If you rip rabbit warrens aim to do this in the cooler months when Carpet Pythons and other reptiles are less likely to be sheltering in warrens.

If you are doing any revegetation at all:

- Aim for a plant density of 20-30 trees per hectare, and include shrubs, native grasses and herbs

- If outcrops are domed or conical shaped consider planting on the southern aspect to maintain basking sites for reptiles

- Reintroduce additional habitat features such as fallen timber and maintain any standing dead plants – including the shrubs.

Find out more…

Sustainable Farms – https://www.sustainablefarms.org.au/resources/

https://www.greeningaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GUIDE_Eucalypt_Woodlands.pdf

Conservation Management Notes Restoring native vegetation (link to come)

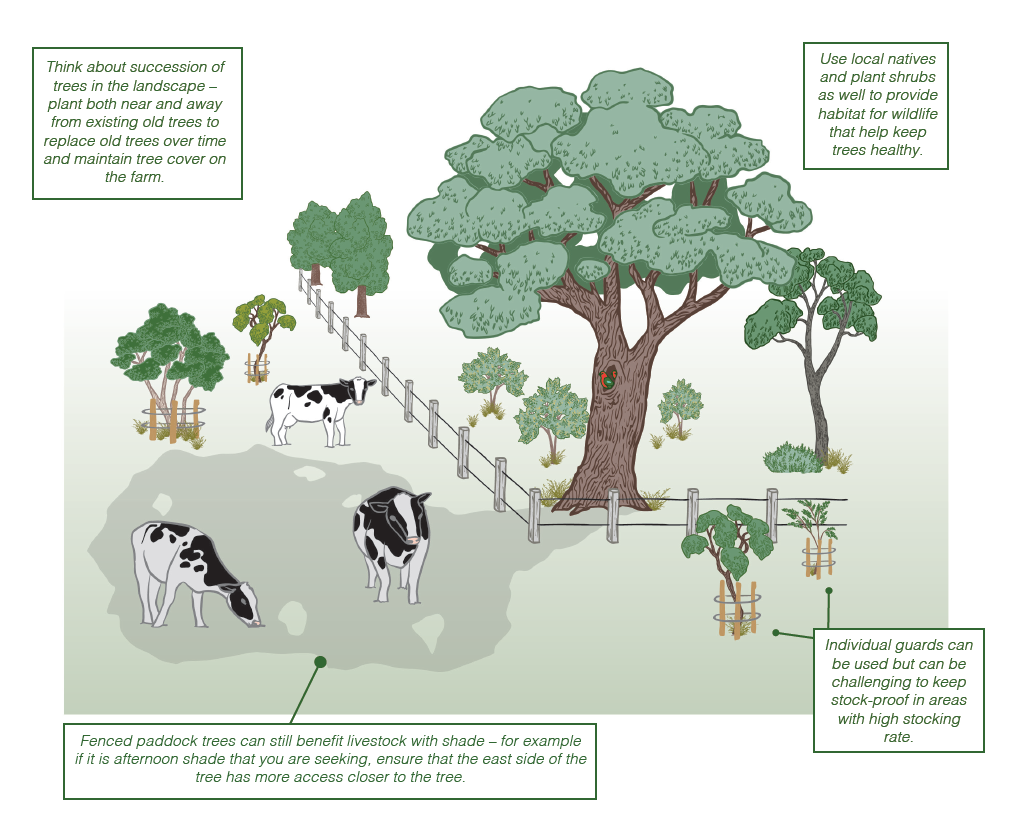

Protecting Paddock Trees and Plantings

The South West Slopes and Riverina is a landscape scattered with large old trees. These trees may be hundreds of years old and provide critical elements in our landscape for livestock and wildlife that cannot be provided by revegetation (see deeper read – Paddock Trees). Protecting and replacing these elders does take effort.

To protect and grow more paddock trees:

- protect individual trees from livestock chewing the bark and camping underneath –use yard panels or gates to exclude them

- fence around paddock trees to exclude livestock; this helps improve the tree’s health by reducing nutrient loads and compaction caused by stock camps

- go wide and outside the drip zone of existing trees to allow natural regeneration; most regeneration occurs at a distance approximately twice the tree’s height away from the trunk

- plant new trees, using individual guards, although they are less cost-efficient.

Paddock tree protection and planting [Adapted with permission: ANU Sustainable Farms]

Taking advantage of a natural regeneration event to protect and increase paddock trees. Photo: D. Grigg

Take advantage of opportunity – if a regeneration event occurs, use it to ensure future paddock trees in the landscape

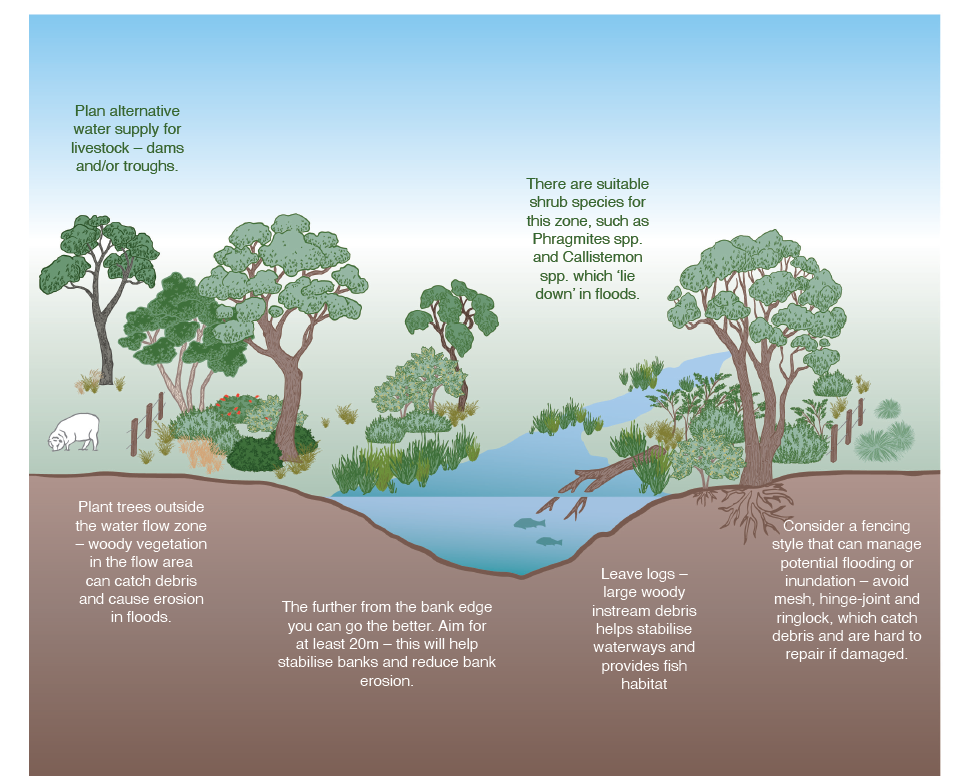

Planting around waterways and in riparian zones

The buffer around waterways is known as the “riparian zone”. These are the most productive areas in the landscape for farming but also for wildlife. These zones have higher productivity for biodiversity than the areas on hills with poorer, drier soils.

Benefits of Well-Vegetated Riparian Zones:

- buffering: riparian zones catch debris and nutrients flowing from nearby land, watercourses, and catchment areas

- stabilizing: riparian vegetation helps stabilize the waterway bed and banks, preventing erosion

- landscape connectivity: vegetated riparian zones are like highways for wildlife – they are long and linear and allow animals to move

- cultural connections: riparian zones are often rich in historical artifacts and resources essential for First Nations cultural practices such as weaving and food gathering.

– MAKING A HEALTHY RIPARIAN AREA –

Making a healthy riparian area [Adapted with permission: ANU Sustainable Farms]

FENCING

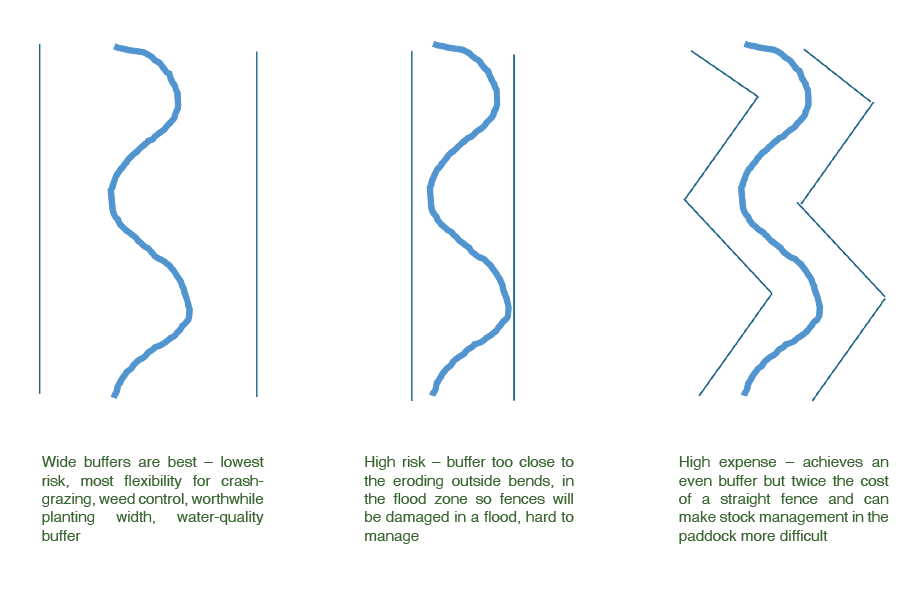

Fencing waterways can be tricky, especially if the stream has multiple channels or lots of bends and there is potential for flooding and any active erosion points.

– FENCING STRATEGIES ON WATERWAYS –

Fencing strategies on waterways

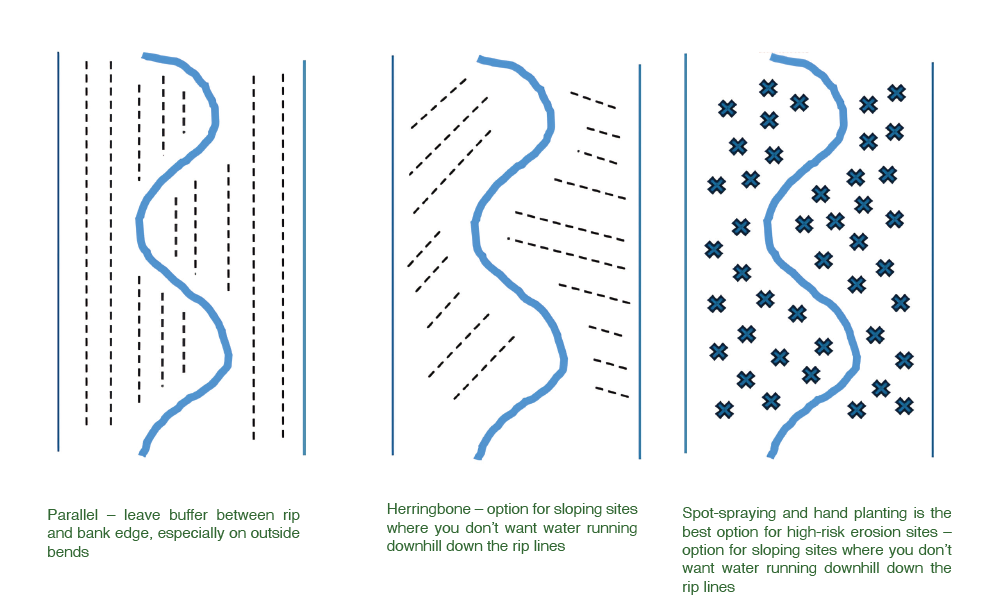

– RIPPING OPTIONS –

Ripping option on waterways

Be aware of the potential requirements for permits for disturbance and vegetation removal within 40m of a stream in NSW.

Seek advice before ripping and spraying complex planting sites to avoid potential erosion. Spot spray, or spray rip lines only to maintain maximum groundcover.

We often concentrate on the top of banks for replanting and rely on livestock exclusion to allow the instream environment to recover by itself. Sometimes they may need active reintroduction.(See Establishing aquatic plants).

Planting overhanging shrubs and fringing plants at the top of the bank is important to be able to restore all the processes necessary for a healthy waterway. These need to be planted by hand, and long-stem planting may be used in sandy banks. (See Figure 12: Planting aquatic and fringing vegetation, and Figure 28: Long-stem planting.)

Find out more…

Greening Australia: A Revegetation Guide for Temperate Riparian Lands – https://www.greeningaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GUIDE_A-revegetation-guide-for-temperate-riparian-lands.pdf

Sustainable Farms: Riparian Restoration – https://www.sustainablefarms.org.au/on-the-farm/riparian-restoration/

NSW DPIE – Controlled activity approvals | Water (nsw.gov.au)

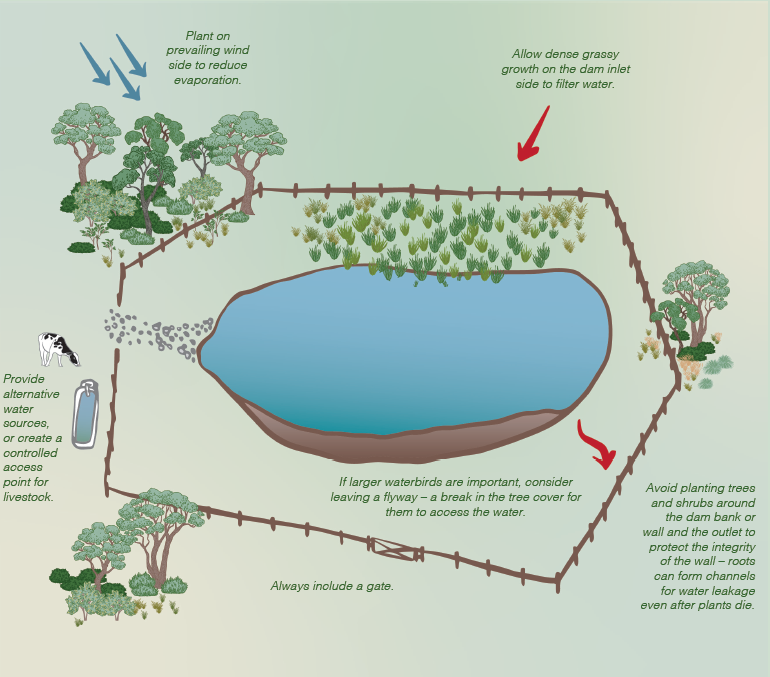

Planting around wetlands and dams

Small wetlands, springs and soaks are common refuges on farms for aquatic species, but they are becoming less common and more degraded.

Farm dams can also be that refuge in the landscape if they are planted and livestock is controlled or removed. Fencing off and planting farm dams, and providing water for livestock with pipes and troughs, has benefits for production by improving water quality and livestock health.

Farm dams as habitat [Adapted with permission: ANU Sustainable Farms]

Farm Dams as Habitat

For natural wetlands the principles are the same, but often the aim for wetlands is restoration, rather than revegetation.

- Fence to control livestock; access and grazing should be limited to when the wetland is completely dry, if at all.

- Assess condition to see if it has the capacity to recover by itself.

- Seek advice about what plants are appropriate. Trees and shrubs do not grow naturally in some types of wetlands. See the following section, Establishing aquatic plants.

Like waterways, wetlands can be rich in historical artifacts and resources essential for First Nations cultural practices such as weaving and food gathering. Research and encourage the plants that support these practices and support a healthy wetland.

Find out more…

Are there plants in your wetlands? (link to come)

Are there seeds in your wetlands? (link to come)

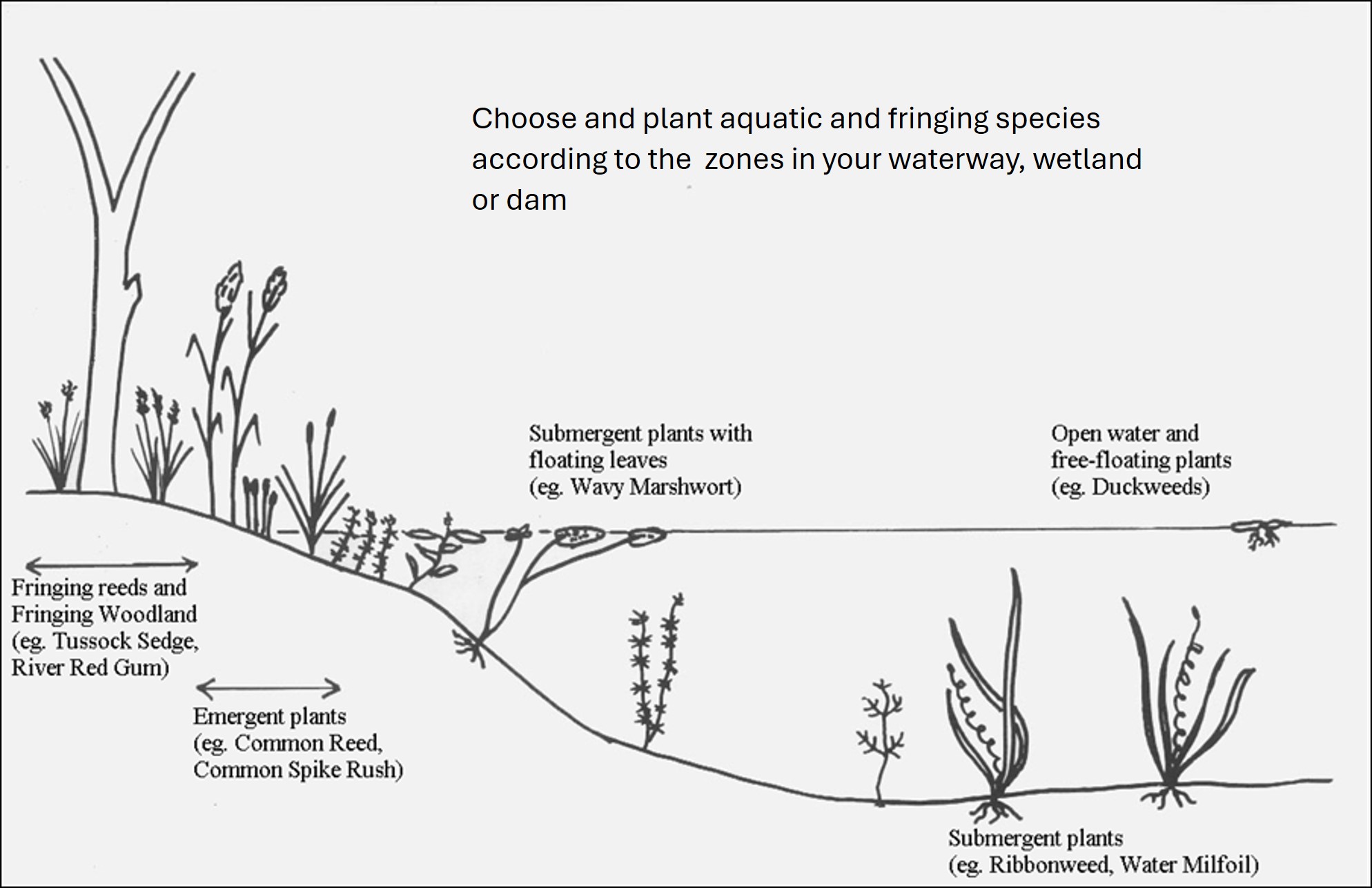

Establishing aquatic vegetation

Aquatic plants growing on the edge and in the water are critical habitat for many aquatic invertebrates, frogs and fish, and are also important for erosion control and traditional cultural practices such as weaving and traditional food gathering for First Nations People.

Revegetation of waterways, wetlands and dams can be challenging if they are highly degraded.

Excluding stock and allowing access for waterbirds and ducks, etc., can help to bring in some species naturally, but you need the conditions for them to thrive:

- a range of depths and substrates (e.g., mud, sand)

- exclusion or control of livestock that trample and graze on plants.

Many aquatic species spread naturally once introduced, so you may not need to do extensive plantings.

Planting aquatic and fringing plants. Source: South West Slopes Revegetation Guide 1st ed – Managing Wetlands

Revegetation can be by:

- Seedlings – there are specialist nurseries that can supply these species

- Seed, cuttings or corms – many aquatic plants will grow from corms or fragments of plants

- Transplanting of rootstock from another location – you have to consider the impact of harvesting, but many rushes and reeds can be quite common and plants can be transferred easily (eg. Phragmites australis – the common reed).

- Transfer of sand or mud with seeds – again, you need to consider the impact on the harvest site, but transferring mud from another site with established plants is possible.

For free-floating plants, sometimes a means to anchor the plants is needed, such as weighting with bricks or rocks. They may also need protection from grazing by yabbies, turtles and ducks.

When planting emergents and submergents, ensure at least a third of the plant is out of the water at the high-water mark.

Restoration of native groundlayer – grasses and forbs

For most farm revegetation we tend to concentrate on trees and shrubs, as these are the most available and the most robust species. Pioneer species like Wattles (Acacia sp.) that are able to establish in the harsh conditions of revegetation – weed competition, high soil nutrient status and unshaded environments.

Often we ignore the groundlayer, or if we do plant them they don’t survive. Groundlayer restoration can be very challenging in highly degraded and modified sites.

Groundlayer plants are:

- native grasses,

- sub-shrubs and tussock plants (small woody plants below 50cm),

- creepers and climbers, and

- small annual leafy plants and wildflowers (forbs).

The technique you use will depend on the site condition.

Highly degraded sites (no native vegetation) – Scalping

Tis technique physically removes the nutrient and weed seed rich topsoil with machinery and then uses hand direct seeding or seedling planting to revegetate.

Considerations:

- It is high risk and expensive.

- Only suitable at low slopes and small scale due to erosion risk.

- It removes soil from the site, so you have to have somewhere to put the spoil.

Less degraded sites

There are a few options:

- management changes – changing the grazing regime, controlling weeds and allowing regeneration

- cultural and ecological burning – research and encourage traditional cultural practices that support a healthy native groundlayer

- planting or seeding missing species directly

- reducing nutrients with a carbon source – there have been experimental techniques that apply carbon (usually sugar) to the site to promote microorganisms to use up the excess nutrients and favour the natives (Smallbone et al., 2007).

Both of these techniques are only suitable for small-scale sites due to both risk and cost, and require a lot of planning and advice.

Do your research and seek advice from Landcare and/or your local regional natural resource management agency.

Euroa Arboretum Grasslands Scrape

(Duration: 3.5 minutes)

FARM SHELTERBELTS

Shelterbelts have benefits for livestock and pastures, including:

- wind protection (hot and cold)

- protection of built assets

- sun protection (shade)

- preventing soil erosion

- managing spray drift

- biosecurity.

There are some very comprehensive resources available around shelterbelts, both hardcopy and online, that can help you design for your specific situation.

Here are some general principles for shelterbelts.

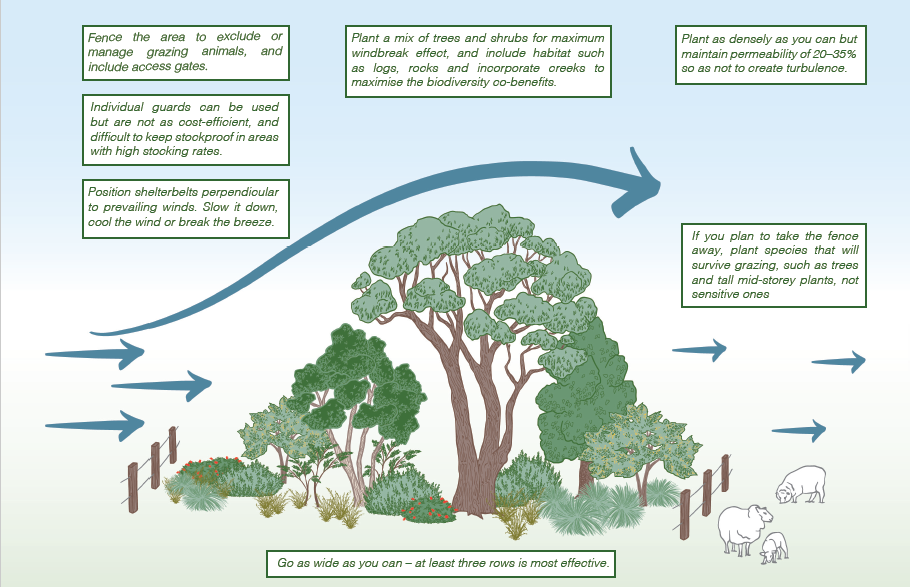

Designing a shelterbelt [Adapted with permission: ANU Sustainable Farms]

Planting Erosion sites

Erosion is caused by the energy of water and wind on the soil. As bare ground is more prone to erosion, the initial aim of rehabilitation and revegetation of any erosion site is to stabilise the erosion (address the cause) and then establish perennial groundcover as soon as possible. Consider the following general points about revegetation of these areas.

- Reduce density of woody plants – heavily planted areas can result in less grass groundcover because of moisture competition.

- Consider the risk of ripping – apply the same principles as for waterways (see Figure 10: Ripping options on waterways) and if you do rip, leave a buffer around active headcuts.

- Create moisture and seed microsites – small banks or shallow disturbances across the contour on the bare ground may be needed where the topsoil may have washed off.

- Mulch may also be helpful in severely degraded sites.

- Consider a cover crop for instant groundcover after earthworks and in highly degraded sites – sterile ryecorn, or an annual cereal may be useful to get instant groundcover and some organic matter back while the revegetation is becoming established.

There are many erosion-control products (e.g. jute matting) available that can help with revegetation establishment on highly degraded sites and recovery after earthworks. Do some research to see if there is something suitable for your site.

Note that in some native ecosystems, some bare ground is natural and the mosses and lichens that grow there are an important part of the ecosystem. These areas should not be targeted for erosion-control actions.

Erosion revegetation using mulch. Photo: Kathie Le Busque

Some bare ground, mosses and lichens is natural in some native ecosystems, and may be a sign of healing and recovery. Photo: Kylie Durant

Planting for dryland salinity management

Dryland salinity is caused by rising groundwater – more water entering groundwater in ‘recharge’ zones, mobilising salt stores and coming back to the surface in a ‘discharge’ zone.

This system can be from local runoff (especially in granitic landscapes) or from irrigation. It can also be regional over many kilometres (metasedimentary landscapes).

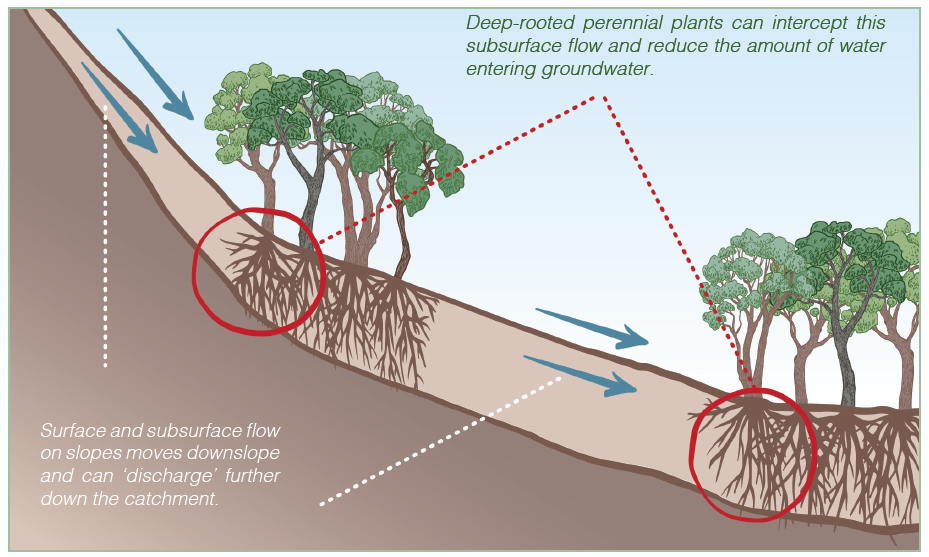

The principle of planting to manage this salinity is to plant to reduce the amount of water entering the groundwater system – plant roots intercepting flow and drawing up water.

Before undertaking plantings for salinity, seek further advice through your local Landcare and/or natural resource management agency, or agricultural advice service. Recommendations can be quite specific to local catchments and sites.

For salinity planting in general:

- Retain and maximise existing woody vegetation and groundcover.

- Revegetate recharge areas with trees and shrubs and/or deep-rooted perennial grasses to reduce the ‘leakage’ into the groundwater.

- Establish ‘break of slope’ plantings – above discharge areas and plant 2–4 rows of trees and shrubs with pastures between (see diagram)

- Buffer discharge sites – fence out the affected area to reduce livestock stock access to allow groundcover to establish and plant woody vegetation around the site. Waterlogged sites may require ripping and mounding.

- Plant saline tolerant species – consider salt-tolerant pasture grass such as Tall wheatgrass and salt-tolerant trees and shrubs.

Example of break of slope plantings for salinity management [Adapted from Clifton et al 2006]

Deep-rooted perennial plants can intercept this subsurface flow and reduce the amount of water entering groundwater.

Surface and subsurface flow on slopes moves downslope and can ‘discharge’ further down the catchment.

Find out more…

Planting for carbon sequestration

Carbon is stored in the stems and roots of woody vegetation and planting it is considered to be a way of storing, or sequestering, carbon in the landscape to offset against the effects of climate change. All revegetation sequesters carbon, but the regulated carbon market has specific requirements of planting that must be followed to be eligible for carbon credits.

There are calculations that project forward the carbon sequestration of a particular plantings depending on the rainfall zone, the species mix and density of planting. This is a developing area that is changing rapidly so it is best to research the planting Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) methodologies at the Australia Government’s Clean Energy Regulator website to get the latest information.

In Australia the regulated market is administered by the Emissions Reduction Fund, the trading units are carbon credits (ACCUs). To create a credit (ACCU), specific methodologies are followed including firstly registering your project prior to any planting activity.

Retrospective credits (i.e for planting already completed or done without prior registration) are not available.

Considerations for planting for carbon sequestration –

- Understand the opportunity on your farm – Use tools such as CSIRO LOOC-C and the AgriFutures Carbon Opportunity Support Tool to reality check for your farm. Does your land have potential or is it even suitable for a carbon sequestration planting?

- Get legal and business advice – is this appropriate for your farming operation and business? Carbon sequestration projects are important business and management decisions.

- Register before you start – You cannot claim credit for work prior to registering a project. There may be design specifications for the methodology you register it under.

Secondary markets are not government regulated and so methods and credit units may differ. This market works by direct negotiation with an investor, and they determine the criteria for planting.

Seek independent advice, talk with your production networks and seek trusted experts for specific property evaluations.

Find out more…

Australian Government Clean Energy Regulator ACCU Scheme methods (link to come)

Carbon farming – NSW Government Climate and Energy Action (link to come)

Net Zero Nature Markets – NSW Government (link to come)

NSW Natural Capital Statement of Intent (link to come)

Greening Australia – What is carbon farming? (link to come)

Western Australia Carbon farming and Land Restoration Program (link to come)

Plantation Farm Forestry

Plantation forestry for on-farm use like firewood plantations can be dual purpose – they can provide great biodiversity, shade and shelter benefits in the short to medium term as well. Collecting firewood from paddock trees and native vegetation is unsustainable and incorporating plantation firewood into the whole-farm plan should be a priority.

Important considerations for plantations are:

- Access – consider access for plantation management (silviculture), access for machinery (planting, management and harvesting machinery), local permissions for use of local road systems for larger vehicles and increased traffic – think about creek crossings, wet areas and how steep the areas are.

- Species selection – Research the most appropriate plant species for the specific plantation purpose, including a reality check on expected growth rates on your site soil type and rainfall zone.

- Business planning – Build in business resilience (insurance) to ensure your forestry asset is covered in the event of a natural disaster such as fire. Budget for several thinning’s that may be required in the life of the plantation to maximise growth rates.

Because there can be short and medium term benefits to biodiversity in a plantation, design to include managing local biodiversity needs – for example, continual cover forestry or linking and complementary biodiversity plantings.

Plantation forests generally contain single species of the same age designed for timber harvest. Photo: K. Durant/HLN.

Find out more…

Murray Region Forestry Hub – https://murrayregionforestryhub.com.au/

Forestry Australia – https://www.forestry.org.au/

Australian Insititute of foresters (link to come)

PLANTING SALTBUSH AND GRAZING SHRUBS

In lower rainfall areas, shrubs are part of the natural grazing system but active revegetation of species like Old Man Saltbush (Atriplex nummularia), especially on saline sites can be done with future grazing in mind.

Considerations

- There are different saltbush species, and it’s essential to select the one that suits your site conditions. Some species tolerate waterlogging and salinity better than others.

- Consult with your agronomist to determine how saltbush fits into your farming system and meets your animal nutrition needs. Keep in mind that stock cannot thrive on saltbush alone.

Planting methods

- You can either plant saltbush as seedlings or directly seed it.

- If using seedlings, prepare fenced blocks where animals can access the saltbush periodically.

- Filler materials: gypsum and vermiculite can be used as fillers during seeding.

Remember that saltbush provides valuable grazing and erosion control, but it’s essential to choose the right approach based on your specific needs and conditions.

Find out more…

NSW DPI: Old Man Saltbush – Factsheet

Mallee Sustainable Farming: Mallee Forage Shrubs Decision Tree – https://msfp.org.au/shrub-decision-tree/

CSU: Native Vegetation of the Riverina – Chapter 7

AgVic – Grazing Management: Perennial Forage Shrubs (Duration: 3:43 minutes)

MANAGING NATIVE GRASSLANDS – RESTORATION NOT REVEGETATION

Grasslands naturally have minimal woody vegetation and should not be the focus of woody species revegetation. If you’re dealing with true native grasslands in the South West Slopes and Riverina regions, keep in mind that they are highly modified. While intact examples are rare, they do exist and typically feature a mix of native grasses, small leafy plants (forbs), and wildflowers.

These areas should be safeguarded from disturbance and changes in fertility. If a grassland has over 50 per cent native species cover, it’s considered protected vegetation. Clearing or altering such areas can lead to compliance actions.

For high quality native grassland:

- Define your goals and create a straightforward management plan with monitoring.

- Instead of planting woody species (like shrubs and trees), focus on managing existing vegetation.

- Control biomass to favour forb and wildflower diversity, and consider reintroducing specific grassland species that are missing. Techniques like slashing, controlled grazing, and prescribed burns can help maintain an appropriate biomass level and prevent loss of diversity.

For a modified, lower quality grassland (e.g., some native species persisting alongside annual weeds):

- Don’t let annuals set seed – crash-graze in spring.

- Reduce grazing pressure during summer when native grasses are setting seed.

- Reintroduce key subshrubs and forb species.

For management of grasslands in general:

- Spread windrows or clumps of grass clippings when mowing or slashing.

- Control weeds that threaten to spread and out-compete or smother native plants.

- Avoid any unnecessary physical disturbance or compaction of the soil – e.g. ploughing, rip lines or trenching.

- Avoid any change to the fertility of the soil – e.g. fertiliser or lime.

- Keep pest animals (grazers and predators) under control or out of native grassland.

- Research traditional cultural practices that support healthy native grasslands like cultural and ecological burning.

If the goal at the site is based on species conservation there may be very specific management requirements. For example, Plains-wanderers need at least 35 per cent bare ground so managers increase may grazing pressure when the grassland habitat becomes too dense.

Examples of various native grassland. Photos: Martin Driver

WHOLE-PADDOCK REHABILITATION

Whole of paddock rehabilitation is a techniques developed by Greening Australia and is designed to integrate large-scale revegetation into commercial grazing or mixed grazing enterprises.

The objective is to revegetate at a paddock scale in a way that can fit with a rotational grazing system. The paddock is taken out of the production system for three to five years and a proportion of the paddock planted with tree and shrub species. It can coincide with pasture renovation or erosion rehabilitation.

When the revegetation is large enough to withstand browsing, a sympathetic grazing rotation reintroduced.

In general:

- The tree belts are not fenced so it is very cost-effective (but you lose grazing for an initial period of time).

- This is most successful in grazing rotations that have a long recovery period (e.g., holistic grazing) or where the paddocks might only be used in certain seasons or for certain classes of stock for one or two rotations per year.

- Revegetation can be by direct seeding or seedling planting.

Contact Greening Australia or talk to Landcare and/or your local regional natural resource management agency.

SEED PRODUCTION AREAS (SPAS)

Seed-production areas are plantings specifically designed and planted for seed collection. As the quantity and quality of native vegetation remnants declines, the need for specific seed-production areas to supply the seed for restoration grows.

In general SPAs:

- Plant particular species and genetic provenance that are deliberately planned and documented to target seed requirements, and to manage any potential inbreeding issues.

- Are designed for easy access for collection i.e. In rows, and often mounded to aid collection.

- Require fencing, regular weed and browsing pest control and pruning.

- Need replacement of aging plants when their production drops off (can be seven to ten years).

If you are interested in seed-production areas, do your research, consult local and regional seed supply users and the Florabank guidelines for seed-production (accessible online).

OTHER TYPES OF PLANTING

Some examples of other types of plantings that are not covered here include native gardens, bush food gardens, commercial flower and foliage plantings and screening plantings. These need to be specifically designed for the purpose and for the site. do your research and seek advice from specialists in the area of interest.